So here’s the plan:

Kamala is going to walk up to Rodney Scott’s Whole Hog BBQ from the left. At 12:50 p.m., Rodney Scott will greet her. She’ll enter through the side door and order at the second register, from the woman in the red shirt. Kamala, Scott, and Maya Harris—that’s Kamala’s sister and campaign chair—will sit and eat. Kamala will then exit through the front door and walk around back to look at the smoker. She’ll reenter through the front, cross the dining room, and exit through the side door to take reporters’ questions.

[soundcloud url=”https://api.soundcloud.com/tracks/601516179?secret_token=s-EkCgB” params=”inverse=true&auto_play=false&show_user=true” width=”100%” height=”20″ iframe=”true” /]

To hear more feature stories, see our full list or get the Audm iPhone app.

Rodney Scott’s Whole Hog, on the corner of King and Grove Streets in Charleston, South Carolina, is perfect—the kind of fast-casual, deeply American spot almost any voter can get behind: local pit master anointed by Anthony Bourdain, outdoor seating under tasteful white Christmas lights, wooden tables with wrought-iron legs, red stools. In the hour leading up to Kamala’s arrival, men walking and biking slowly down Grove Street give way to police cars, followed by unmarked cars. At T minus 10, the campaign’s 23-year-old South Carolina communications director, Jerusalem Demsas, asks, “Can we get Rodney out here?” She places Scott, handsome and regionally beloved, on his mark to the left of the door. After Demsas leaves, Scott mutters, “People with warrants must be running off the block.”

It’s all happening before you can even see her, so thick and aggressive is the press: the 20-plus reporters with TV cameras, boom mics, lenses larger than some dogs. Kamala shakes Scott’s hand; touches his arm; smiles her big, open, I-am-so-happy-to-be-with-you-right-now smile. She’s shorter, even in heels, than one expects. But she’s magnetic, authoritative, warm—leaning in, nodding, gesturing with both hands, moving those hands from a voter’s biceps or shoulder to a position of deep appreciation over her heart.

Kamala wends through the scrum of press, makes her way to the counter, and finds the woman in the red shirt, who happens to be Scott’s wife. Kamala greets her with a two-handed clasp (a simple shake would come across as too formal and masculine). Then, right there, a decision needs to be made on the fly: What is Kamala going to order?

Kamala Harris—the Democratic presidential hopeful and 54-year-old junior senator from California—is a prosecutor by training. She knows well that any misstep, anything you say or do, can and will be held against you. Her fundamental, almost constitutional, understanding of this has made her cautious, at times enragingly so.

Harris’s demographic identity has always been radical. She was San Francisco’s first female district attorney, first black district attorney, first Asian American district attorney. She was then California’s first female attorney general, first black attorney general, first Asian American attorney general. She was the second black woman, ever, to win a seat in the United States Senate. But in office, she’s avoided saying or doing much that could be held against her. As attorney general, she declined to support two ballot measures to end the death penalty. She declined to support making drug possession a misdemeanor. She declined to support legalizing pot. She declined to support a ballot measure reforming California’s brutal three-strikes law. The point is: She had power. She kept most of it in reserve. More important than fixing the broken criminal-justice system, it seemed, was protecting her status as a rising star. She had earned that reputation by the time the first major profile of her was written: San Francisco Magazine, 2007. The article also described her as “maddeningly elusive.”

It takes Harris a minute, but she decides on a pulled-pork sandwich, with corn bread and collard greens, and a banana pudding to split with Maya. They sit and eat, ignoring the two dozen recording devices in their faces, talking about Scott’s vinegar-based BBQ sauce and his recipe for banana pudding—good territory for Harris, as she’s a serious cook. Nearby, there are a few appalled customers, including a family that has driven 40 minutes to celebrate the father’s birthday and has no idea what’s happening, no idea even who Harris is, and would just like this rugby squad of reporters to move aside long enough for their son to refill his drink. But for the most part, the patrons are dazzled by Harris, whose star quality drew 20,000 people to her kickoff rally in Oakland. The dynamism she displayed there made the event feel like a cause, or a concert—Kamalapalooza—and gave her campaign significant momentum. (Laurene Powell Jobs, the president of Emerson Collective, which is the majority owner of The Atlantic, has provided financial support to the Harris campaign.)

After 15 minutes, right on schedule, Harris sets down her napkin and walks around back. She takes some photos near the smoker with Scott’s family and looks deeply into the eyes of his adorable 10-year-old son. She tells him she’s giving a speech later and she’d like him to let her know what he thinks of it. Then she walks back through the restaurant and exits, as planned, through the side door so she can gaggle with the press. (NB: Gaggle is now a verb in American politics, meaning “to answer questions shouted at you by a group of reporters.”)

Here, again, Harris is graciously, militarily on point. All good politicians stick to a script, but Harris speaks like a woman who knows that facts are ammunition. Everything you say can and will be used against you. Just this week she’s been in the weeds, so to speak, with Reefergate, a kerfuffle that arose when Harris was asked on the Breakfast Club radio show what music she’d listened to when she smoked pot in college and she said Tupac and Snoop Dogg. Social media erupted with gotchas, as those artists didn’t release songs until after she’d graduated.

Harris’s spokesperson said that she’d been answering a different question, about the music she listens to now, but even so The New York Times, The View, MSNBC, and Fox & Friends all picked up the story. Harris’s own father, who is Jamaican, flamed her on Jamaica Global Online for insinuating that she supported legalized pot because she was Jamaican: “My dear departed grandmothers … as well as my deceased parents, must be turning in their grave right now to see their family’s name, reputation and proud Jamaican identity being connected, in any way, jokingly or not with the fraudulent stereotype of a pot-smoking joy seeker.” The uproar caused the former Obama speechwriter Jon Favreau to flip out on Pod Save America: “Donald Trump is president … We cannot be talking about this fucking shit again with the Democratic candidates.”

But Harris, today, gaggling, is in top form: We don’t need a tragedy to enact commonsense gun reform. This economy is not working for working people. Every American needs a path to success. We need to speak truth. If Harris’s campaign has a mantra, that’s it: truth truth truth truth truth. She delivers her talking points while dressed, as she always is, in her uniform of dark suit, pearls, black heels. I know—you think I shouldn’t be writing about her clothes. But the clothes themselves are a smart, cautious play, one that Hillary Clinton, frankly, could have benefited from. If you wear the same outfit every single day, pretty soon the haters will run out of snarky things to say about your appearance and move on.

[Jemele Hill: Kamala Harris’s blackness isn’t up for debate]

Among Harris’s core traits, arguably her Shakespearean-tragedy trait, the one so central to her character that it has the potential to lift her to the highest post in the land but could also take her down, is her discipline. It is what has allowed her to play the long game, to protect her future. It has also infuriated constituents over the years who wanted Harris to take a stand and fight for them today, not when she reached a higher office. Yet Harris, on the trail, seems bolder than she has in the past. She’s declared that she’s for reparations, for the Green New Deal, for decriminalizing sex work and legalizing pot. She comes across as a woman who is cashing in her chips, taking all the political and social capital she was safeguarding for all those years and putting it on the table, declaring that her moment is now. She’s a black female prosecutor; we have a racist, misogynist, possibly criminal president. All of that caretaking of her political future—what was it for if not this?

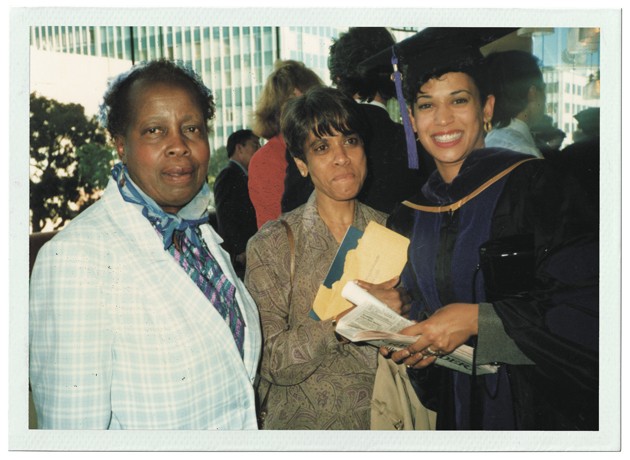

By Harris’s side, on the road, is not her husband, Doug Emhoff, a Los Angeles lawyer she married in 2014, but her sister, Maya, who was a top policy adviser for Hillary Clinton’s 2016 presidential campaign and, before that, the vice president for democracy, rights, and justice at the Ford Foundation and the executive director of the ACLU of Northern California. When the world is following you with boom mics and long knives, Maya told me, “it’s good to know there are people with you 100 percent. Ride or die. Not going anywhere.”

Harris’s parents, Shyamala Gopalan and Donald Harris, met in Berkeley, California, in the early 1960s, in the civil-rights movement. They’d both come to the United States to study at UC Berkeley: Shyamala, at age 19, from a Brahman family in India, to pursue a doctorate in endocrinology and nutrition; Donald, from Jamaica, for a doctorate in economics. As with almost everything else in her life, Harris has a set of stock stories she tells about her upbringing, all of which are laid out in her heavily vetted, surprise-free memoir, The Truths We Hold, which was released two weeks before she announced her candidacy. (The big vulnerable reveal in it is that Harris had to take the bar exam twice.) As a girl, she loved the outdoors; her father yelled at her, “Run, Kamala! As fast as you can. Run!” Her mother sang along to Aretha Franklin; her dad played Thelonious Monk. They divorced when Harris was 7. Before that, the family attended protests together. At one, Harris, a toddler, started fussing. Her mother bent down and asked, “What do you want?”

Harris said, “Fweedom!”

Shyamala, the daughter of a diplomat father and a mother who educated fellow Indian women about birth control through a bullhorn, was barely 5 feet tall, and formidable. She was supposed to return to India for an arranged marriage. She refused. “She had literally no patience for mediocrity,” Maya said. Her outlook was: “Be your best. If you’re going to do something, be the best. Work hard, the whole way.” En route to becoming a prominent breast-cancer researcher, she raised her girls primarily as a single mother. She took Harris with her to her lab when necessary and directed her to wash test tubes. She covered the kitchen in their small apartment with waxed paper and made lollipops and other candy. If she bought gifts, she set up a game in the style of Let’s Make a Deal. What do you want—Door No. 1 (the bedroom) or Door No. 2 (the kitchen)? Inside, the girls would find a blue bike with tasseled handlebars or an Easy-Bake Oven. In Harris’s telling, Shyamala didn’t coddle. If her children came home from school with a problem, she would ask, “Well, what did you do?,” in order to push them to solve it themselves. She raised her daughters in the black community, taking them to Berkeley’s black cultural center, Rainbow Sign, where Maya Angelou read poetry and Nina Simone sang. In 1971, when Harris was 7, Shirley Chisholm dropped by. She was exploring a bid for president.

When I asked Maya about her relationship with her sister, Kamala raised her eyebrows and cocked her head, like, This had better be good. “Well, she’s a big sister and …” Maya paused and turned to Harris. “Are you going to qualify that?”

Harris, laughing, declined. So Maya continued: “She was protective … Maybe just a liiiiiiiittle bossy.” If there was a problem in the schoolyard, Harris would assess the situation and make sure Maya was okay. The two organized a children’s protest to overturn a no-playing policy in their apartment building’s empty courtyard. Do I even need to say it? They won.

When Harris was in middle school, Shyamala took a post at McGill University and moved with her daughters to Montreal. Harris attended high school there. At Howard University, in Washington, D.C., she chaired the economics society, argued on the debate team, and pledged the AKA sorority, the first black sorority in the country, whose alumnae show up at Harris’s campaign events in force, dressed in AKA pale pink and green, a squadron of extra aunts. At UC Hastings College of the Law, in San Francisco, Harris “found her calling,” as she writes in her memoir, and decided to become a prosecutor.

This was not an easy sell for her parents. Shyamala believed, as Harris writes, that America had “a deep and dark history of people using the power of the prosecutor as an instrument of injustice.” Among Shyamala’s closest friends was Mary Lewis, a professor and public intellectual who helped lead the black-consciousness movement in the Bay Area. Donald Harris, meanwhile, had become an economics professor at Stanford University, the first black man in his department and one of about 10 black faculty members total. He was a left-leaning iconoclast who wrote and taught about uneven economic development around the world, particularly across racial lines, long before many Americans had ever heard the phrase income inequality. Colleagues found his progressivism threatening—he was called “too charismatic, a pied piper leading students away from neoclassical economics,” in The Stanford Daily.

Yet growing up at protests, Harris writes, she’d seen the mechanics of fighting for “justice from the outside.” That dynamic did not appeal to her. She wanted insider power, establishment power. “When activists came marching and banging on doors,” Harris writes, “I wanted to be on the other side to let them in.” Shyamala interrogated this logic. As Harris says, both in her book and in speeches, “I had to defend my choice as one would a thesis.”

It was the choice of a woman who likes control. Even sitting with Maya, post-barbecue, in a corridor of a black church in South Carolina before a town hall—when Harris is laughing and slightly slouched in her chair, seemingly relaxed—she’s a woman who maintains a tight grip on the narrative. No detail is too small.

“I stay with her a lot when I’m in D.C.,” Maya says, trying to tell me a story about how Harris likes to take care of people. (I experienced this myself. I showed up that day with a cough, and Harris instantly offered me cough drops and green tea.)

Harris corrects Maya, quietly but firmly: “Always.”

“Always … almost always,” Maya says. “Okay, mostly.”

Harris stands her ground: “Always.”

Maya—a Stanford Law School grad and one of the youngest people ever appointed dean of a law school—drops the point.

Harris will talk about cooking, specifically and in great detail, if you ask her. She’ll even get out her iPad and show you the recipes she’s marked from The New York Times’ cooking section, which she reads in the campaign van, after events, to relax. Chicken Cacciatore With Mushrooms, Tomatoes, and Wine—what’s oppo research going to do with that? I can tell you that her go-to dinner is roast chicken and that she’s cooked almost every recipe in Alice Waters’s The Art of Simple Food. In the kitchen, she’s a fundamentalist. “Salt, olive oil, a lemon, garlic, pepper, some good mustard—you can do almost anything with those ingredients.”

But turn the discussion to this moment in her life, to taking her shot—how she’s going to both protect this opportunity and go all out; where the line is between being too cautious and too open—and the specificity disappears. First she pivots away from caution. “I wouldn’t say cautious as much as smart. We have to be smart. We have to be strategic.” (This is a favorite move. For more than a decade Harris has talked about being “smart” on crime rather than “tough” or “soft.”) Then she turns to truth. “We have to speak truths, and in speaking those truths, some people are surprised that I’m actually saying that on a stage … So we have to push it.”

Lord knows we are all desperate for a president who values truth. But that wasn’t what I was getting at. There are a great many truths in the world. I wanted to know which ones were on her mind. Where is she going to be bold? Where does she feel she needs to hold back?

[Read: How Kamala Harris is running against 2020 democrats]

“I guess a lot of how I decide [what to] talk about is based on what people tell me they want to discuss,” Harris says. “Not so much what they want to discuss as what are the concerns for them.” This is going nowhere. “Certainly I do think in specifics. And when I’m in a smaller group where there’s more latitude to have a real conversation …”

I have limited time. I drop the question and move on, which of course was Harris’s goal.

It is truly a shame that Shyamala Gopalan isn’t here for this—her two daughters together, Kamala running for president of the United States.

She died 10 years ago. She had colon cancer, and when the end was near, Harris visited her in the hospital while running for attorney general. “She was starting to tune things out. She’d stopped watching the news and reading the paper, which was so unlike her, and she was tired. She was sleeping a lot. And I was with her in the hospital. I was sitting next to her—here’s the bed,” Harris says, motioning to her side, “and she was turned that way. We were just spending time together. And she said, looking away, with her eyes closed, I’m sure: ‘What’s going on with the campaign?’

“I said, ‘Well, Mommy, they said they’re gonna kick my ass.’ My mother leaned over and looked at me and had the biggest smile. Just the biggest smile on her face.”

Harris laughs. I ask what the smile meant. She says, “Bring it on. Good luck to them.”

America—at least the blue parts—came to see Harris as its potential savior in June 2017, when she questioned then–Attorney General Jeff Sessions about the Russia investigation. Sessions sat at a desk before the Senate Intelligence Committee, his mouth pursed in a boyish smirk, his white hair looking as though his mother had combed it for him, Harris regal on the dais above. Here was a man thinking he was going to get away with something, as he nearly always had. Then, in view of the world and this very smart black woman 18 years his junior, he began to realize he was not.

Harris, detailed notes in hand, had no patience for his “I do not recall”s and his long-winded responses to run out the clock. She just calmly and repeatedly demanded an answer to her question: “Did you have any communication with any Russian businessmen or any Russian nationals?” Her mental clarity was terrifying.

Sessions broke down after three and a half minutes. “I’m not able to be rushed this fast!,” he said. “It makes me nervous.”

Justice Brett Kavanaugh’s Supreme Court confirmation hearings, in September 2018, cemented many Americans’ belief that Harris was the woman to go after Trump. “Have you discussed [Special Counsel Robert] Mueller or his investigation with anyone at Kasowitz Benson Torres, the law firm founded by Marc Kasowitz, President Trump’s personal lawyer?”

Harris—who, like any good prosecutor, knows not to pose a question to which she doesn’t already have the answer—asked this nearly verbatim six times, shining a hot and unflattering spotlight on Kavanaugh, who responded, in order, as capillaries appeared to burst all over his face:

1. “Ah …”

2. “I’m not remembering, but if you have something …”

3. “Kasowitz? Benson? …”

4. “Is there a person you’re talking about?”

5. “I’m not remembering, but I’m happy to be refreshed or if you want to tell me who you’re thinking of …”

6. “Do I know anyone who works at that firm? I might know … I would like to know the person you’re thinking of.”

Harris then said, “I think you’re thinking of someone and you don’t want to tell us.” Finally Senator Mike Lee of Utah raised an objection and stalled her line of questioning.

Historically, the prosecutor’s office has been a hard place to run from on the left. You will never really be the progressive. By definition, you are defending the state. On the stump, Harris reframes her prosecutorial role: “My whole life, I’ve only had one client: the people,” which sounds nice coming from the mouth of a public servant. What voter is not for that? Yet when Harris entered a courtroom stating that she was there to argue “for the people,” she was not the voice of the underdog. She was the voice of enforcement, the voice of the law.

Jeff Adachi, the city’s longtime elected public defender (who died of an apparent heart attack at age 59 not long after I interviewed him for this article), met Harris when she was a first-year law student at Hastings. “Did she always have the charm and ambition she’s known for today? Yeah,” he told me. Adachi was “a little surprised,” he said, when Harris aligned herself “with law enforcement and wanting to put people behind bars,” because “we had probably talked about politics before and she was always seen as more of a liberal progressive.” But there were very few prosecutors of color at the time, and very few women, and, Adachi said, the prosecutor path was “seen as a stepping stone to do something bigger or greater.”

When Harris ran for district attorney, in 2003, she challenged Terence Hallinan, her former boss, from the right. He was entangled in Fajitagate, a preposterous scandal that involved three off-duty police officers beating up two residents and then demanding their takeout fajitas. The public saw the department as an unprofessional and incompetent bunch of good ol’ boys. (Hallinan had a low conviction rate, and he did not help his reputation when he handed members of the Fajitagate grand jury a blank indictment form and asked them to fill in the names of the officers they thought should be charged.) Harris enlisted her mother to stuff envelopes and brought an ironing board to neighborhood campaign stops, to use as a portable table. She wasn’t a natural. She felt awkward talking about herself with strangers.

She’d had a much-discussed relationship with future San Francisco Mayor Willie Brown, who was 31 years older and estranged from his wife. Brown was a local kingmaker. Still, Harris did not assume that he would anoint her. During the campaign, her longtime mentee Lateefah Simon took a BART train into the Mission early one weekday. “It’s, like, 7:30 in the morning—legit,” she told me. “I’m coming up the escalator and I see Kamala Harris, by herself, in a suit at 16th and Mission.” The intersection then smelled like feces and was filled with drug dealers. Simon looked at Harris like, Are you stupid? What are you doing here, dressed like that, when people are still high from the night before?

“I’m trying to win this race!” Harris told her.

“She had on pearls!,” Simon said.

Once in office, Harris got straight to work cleaning up Hallinan’s mess. She painted the office walls, which no one had done in years. She replaced the jam-prone copy machine. If staffers tried to leave for the evening before Harris thought they should, she shouted, “Well, I guess justice has been done! Everybody’s going home.”

She endured one major scandal, over a rogue tech in her crime lab. The tech stole cocaine and mishandled evidence, which was bad enough. But then Harris, likely thinking she could address the issue quietly, failed to follow procedure and inform the defense lawyers in the cases involved. One thousand cases had to be thrown out.

Nevertheless, in her first three years as DA, San Francisco’s conviction rate rose from 52 to 67 percent. She even created a new category of crime—truancy—and punished parents who failed to send their children to school. Then, as now, no one contested the link between high-school graduation and a person’s future in a well-paying job as opposed to jail. Harris still talks about this. She stirs outrage at America’s collective failure to invest in the education of other people’s children, often citing the statistic that nearly 80 percent of all prisoners are high-school dropouts or GED recipients. But is arresting a mother whose life is so frayed that she can’t get her child to school the best way to set that child on the path to success? Many, particularly in the black community, answered no. They still do. “Identity politics is stupid,” says Phoenix Calida, a co-host of The Black Podcast, “if you’re not going to enact identity policy.”

Harris ran against the death penalty, and, in what was arguably the first and last truly controversial decision she’s made in her political career, she stuck to her position and did not seek capital punishment when a San Francisco cop was killed in the line of duty several months into her tenure. The pressure to reverse her campaign promise was intense. Senator Dianne Feinstein, who’d served as San Francisco’s mayor from 1978 to 1988, chastised Harris for not doing so at the slain officer’s funeral.

Still, Harris kept her promise—and paid for it. No police union endorsed her for 10 years. One plausible read of her political history suggests that this experience, less than a year into elected office, taught her to fear and avoid taking a stand.

Harris calls herself a progressive prosecutor, which she’s not, though she did lift up individual lives. She started one of the first prisoner reentry programs in the country, Back on Track. It helped young, first-time drug offenders find jobs and services and earn high-school degrees. But Back on Track served only 300 people; Harris never took the program to scale. She also mentored young women, among them Lateefah Simon, who went from being a high-school dropout to becoming a MacArthur genius-grant winner in 10 years, which has got to be a record.

Simon now runs the Akonadi Foundation, in Oakland, dedicated to eliminating structural racism. The two met when Simon was 22 years old, with a 4-year-old daughter. At the time, Harris was running a child-exploitation task force; Simon showed up at a meeting to advocate for young women who’d been trafficked by pimps and then charged with prostitution instead of being treated as victims of rape. Harris listened to Simon, recognized her intelligence, and took her potential seriously. “I was like, Who is this woman? No one listens to us,” Simon told me. “People hate us. We’re garbage, in policy and in public.”

Harris helped Simon raise money and throw events for her organization. She insisted that Simon enroll in college, and when Simon said that was impossible—she was already working and raising a daughter alone—Harris talked about Maya, who’d had a daughter herself at age 17 and then graduated from UC Berkeley and Stanford Law School. The powerful, polished black woman who believed that Simon could be a powerful, polished black woman too blew Simon’s mind: “This was before Olivia Pope!” But Harris’s role as DA took some getting used to. “Why would you want to do that?” Simon asked. “I so deeply knew what was happening with girls in the system, and the DA was our nemesis. The DA and the pimp, right? The DA and the pimp.”

Harris’s race for California attorney general was extremely tight—so tight that her opponent, Steve Cooley, gave a victory speech on Election Night, which he had to retract the next day. She campaigned as a progressive, figuring, perhaps, that many people think they support criminal-justice reform more than they actually do. “They like these talking points and these platitudes,” Phoenix Calida says. Let’s be smart on crime. “But her tough-on-crime policies—nobody’s really gonna complain, because they feel safe.”

Harris’s record in that office is marked more by what she didn’t do than what she did. She did not support a ballot initiative reforming California’s three-strikes law, which incarcerated people for life for petty crimes (an interesting family moment, because Maya, while working at the ACLU of Northern California, had championed a proposition to take three strikes down). She did not join the fight against solitary confinement. She did not support two state ballot propositions to end the death penalty (and when a federal court in California struck down the death penalty as unconstitutional, she appealed the decision). She did not support legalizing pot. She did not advocate for reopening several high-profile cases, including a capital one widely suspected to have resulted in a wrongful conviction. She did not prosecute Steven Mnuchin, the CEO of OneWest Bank and Trump’s pick for Treasury secretary, for more than 1,000 foreclosure violations. She did not take an aggressive stance on officer-involved shootings—most notably, she did not endorse a bill requiring independent investigations of them and declined to use the power of the office to investigate the killing of Mario Woods, who was shot 26 times by five police officers in 2015.

Harris has since taken strong progressive positions. But some of her constituents still feel burned. “California has had the most police killings, and we haven’t had any officers ever charged,” Tanya Faison, the lead organizer for Sacramento’s Black Lives Matter chapter, told me. “That was on her watch.” Sure, “it would be beautiful to have a black woman as the president,” Faison continued. But “it doesn’t matter if you’re black or not if your policies are not for black people. And her policies are not supportive of black families.”

To be fair, while in office, Harris did institute implicit-bias training for police officers. She did test a large backlog of rape kits. And she did negotiate well with the nation’s five largest mortgage firms in the aftermath of the 2008 economic crisis. She walked away from an offer of $4 billion of debt relief for California homeowners and called Jamie Dimon, the chairman of JPMorgan Chase. She told him his side needed to come up with more money, much more. She ended up with $20 billion.

She won her Senate seat on the night Trump was elected. By then Harris was walking the line she’s on now: using “fearless” as a campaign slogan despite letting fear stop her from taking positions. Trump has been a productive foil for her, highlighting the value of her legal training, casting her discipline as flattering and calm rather than pinched and nervous.

In Washington, she hasn’t done much—let’s be honest, who in the Senate has in recent years? She introduced a few bills: one, with Kentucky Republican Rand Paul, to study reforming the cash-bail system; another, with 13 Democratic colleagues, to begin addressing the high mortality rates black women face in childbirth. She also introduced, with fellow Democratic presidential candidate Cory Booker and Republican Tim Scott, a bill to make lynching a hate crime. This last one was classic Harris: tough on crime, seemingly progressive, entirely risk-free. It passed the Senate unanimously.

By 4:30 p.m., 1,000 people had packed into the gym of Charleston’s Royal Missionary Baptist Church, where the scoreboard read 2020 and AKA sorority sisters rolled in wearing full pink-and-green dress uniform. They are not even a little ambivalent about their candidate. She’s theirs; they love her. Who among us hasn’t been scarred by an early humiliation and retreated from hard decisions? They asked where the reserved AKA section was.

Backstage, Harris chatted her way through the photo line, a mainstay of the contemporary American political campaign: local officials and other VIPs get what is basically a school photo with the candidate—in this case, next to a state flag, backed by a royal-blue drape. She has an amazing ability to focus on the person right in front of her, even as a large and impatient crowd claps and shouts “KA-MA-LA” for her to come onstage.

“I ate with Rodney Scott today, so I’m happy,” Harris announced to cheers when she finally appeared. Microphone in hand, she slipped into a subtle southern accent. “We have to restore in our country truth and justice, truth and justice,” she said. The crowd, right there with her, called out: “Amen!” “That’s right!”

This Charleston event was a 1/20th-scale model of Harris’s campaign-kickoff rally in Oakland. There, Harris had clapped along with her 20,000 supporters as she made her way to the podium. Just the sight of a strong female candidate who was not Clinton came as a relief. Many Democrats remain traumatized by 2016, the matchup of a deliberate and dutiful woman, straining to mop up all messes, against an impetuous, state-trashing bully. But in dropping her guard a little, Harris has been trending away from Clinton and toward Michelle Obama—adopting a persona that’s less programmed, hipper, and more relaxed, all of which is more likable. Of course, we care intensely about likability, especially in our female candidates, so perhaps shucking the appearance of restraint is a prudent A-student decision as well.

Harris’s campaign is shorter on specifics than Clinton’s was (perhaps, again, in reaction to Clinton). It’s shorter on specifics than some of her fellow 2020 candidates’ campaigns, though she did lay out, in her Oakland speech, a basic platform, designed to appeal to a liberal base, not attract independents: Medicare for all; universal pre-K and debt-free college; a $500-a-month tax cut for low-income families; women’s reproductive rights; a path to citizenship for immigrants.

Then, at minute 32 of the speech, in a moment that managed to be both subtle and shocking, Harris addressed the thing almost nobody wants to say but everybody who is close to Harris thinks about: her personal risk. “As Robert Kennedy many years ago said, ‘Only those who dare to fail greatly can ever achieve greatly.’ He also said, ‘I do not lightly dismiss the dangers and the difficulties of challenging an incumbent president, but these are not ordinary times, and this is not an ordinary election.’ ”

That line passed, and Harris moved on to pablum like “Let’s remember: In this fight we have the power of the people.” But Harris is a target. She knows it. Reports of hate crimes increased 17 percent during Trump’s first year in office. In late February, a Coast Guard officer was accused of plotting to kill Harris, along with 19 others, including journalists, activists, and Democratic politicians. The very fact of her campaign, Harris standing out there every day before crowds of thousands, presenting herself to the American people—some of whom will merely dissect her record; others of whom will see her female body and her brown skin, and want her dead—is bold and brave. “Through her career it’s been a very serious thing,” Harris’s close friend and adviser Debbie Mesloh told me. “She and I talked about it [regarding] Obama … The first day he had Secret Service. The first time I saw him in a bulletproof vest.” Even at the relatively small book talk Harris gave at the cozy Wilshire Ebell Theatre, in Los Angeles, a security guard stood behind her, not even off in the wings, visible to the audience the whole time.

After Harris finished speaking in Oakland, her family joined her onstage: her husband, Doug, who is white; her sister, Maya; Maya’s husband, Tony West, who is black (and currently the chief legal officer at Uber, formerly the third lawyer from the top in Obama’s Justice Department); Maya’s daughter, Meena; Meena’s partner and children. The family is beautiful and the family looks like the future—and not the future in which white nationalists win.

It’s hard not to be ambivalent about a cautious person, particularly a person who has been working for you but holding back, saving for the future. In truth, it’s hard not to feel ambivalent about all the candidates. There are so many contenders, more of them popping up like white-haired crocuses every day. One is too old. (Well, two are too old.) One’s too mean to her staff. One said she was Native American and she’s not. One Instagrammed his trip to the dentist. So many Americans have conflicting desires for this election. They want a transformative leader who will push this country forward. They want a rescue, a captain to steady our faltering ship of state and restore the rule of law. Most of all, they want a winner—whoever that is, just tell them, they’ll vote that way. They want a sure thing. They need a sure thing. And then they feel scared and frustrated by all the options, because that’s not how the system works.

Among the many lines Harris offers on the stump is: I intend to win this. You don’t quite expect to hear a woman say that. But Harris has become very good at tapping into the emotions of a crowd of Democrats and delivering what they want to hear. The 2020 Democratic National Convention is 15 months off, though. Over the next year, the campaign is sure to get ugly—Trump hasn’t even given Harris a nickname yet. I asked her whether she thought that, as a black woman, she had an extra-narrow lane of acceptable behavior to maneuver in. “I don’t think so,” she said. Then she downgraded that sentiment. “I hope not.”

Has the United States dealt with its own racism and misogyny enough to elect a black woman president? There’s little rational basis for saying yes. But there was little rational basis for believing that a man named Barack Hussein Obama could win the White House either, let alone a huckster named Donald Trump.

That Friday night, on the 110-mile ride from Charleston to Columbia, South Carolina, Harris read recipes online. She flagged one for salted-caramel cookies and emailed it to Lily Adams, her communications director, who happens to be former Texas Governor Ann Richards’s granddaughter. (Adams later laughed and said, with genuine affection, “When do you think I’m going to bake these? I’m going to New Hampshire with you on Monday.”)

In the morning Harris, Maya, and Adams, and the whole rugby team of journalists, met up on Columbia’s Lady Street—yes, Lady Street—for some retail politics. First stop was Styled by Naida, a vintage-clothing store run by Naida Rutherford, who grew up in the foster-care system and was homeless before she steadied herself economically by hosting stylish garage sales. It was another ideal campaign stop: Rutherford, the success story, helped Harris pick out a hat and a black belt. Then, as Maya paid for the items, Harris noticed a brightly colored sequined coat, a chessboard of turquoise, purple, yellow, green, and sky blue. The jacket was just about the furthest fashion choice imaginable from Harris’s standard dark blazer. Still, Rutherford, a good saleswoman, encouraged Harris, a good candidate, to try it on, and Harris did. She looked in the mirror, the hoard of journalists to her back. “This really would be perfect for the Pride parade,” she said.

A nice, unguarded human moment. The jacket was way too big, and she’ll almost certainly never wear it anywhere but the parade. But you’d have to be a monster—and a tone-deaf politician—not to want to support Rutherford. Harris bought the coat.

That afternoon, Harris held another town hall, this time at Columbia’s Brookland Baptist Church, and sitting in her car in the church parking lot, waiting for the doors to open, was 77-year-old Gladys Carter. Carter had fought in the civil-rights movement. She was heartbroken and horrified by the turn her country had taken with Trump’s election, and she admired how Harris had handled Kavanaugh. But she had questions about criminal justice. “Some African Americans in my circle of friends have expressed concern about her actually imprisoning a lot of our people, more so than she did the others,” Carter said. “They say they have to really think hard before they’re able to trust her. She’s got to prove that she’s willing to come out and do some things differently.” At the same time, Carter felt that Americans have deeper, even more pressing problems—namely, our dangerous, lying president. Maybe a tough female prosecutor is our best hope. “This country has been controlled by white males for how many years? The way things are right now—they screwed it up.”

Harris made it home for dinner with her husband that evening. She slept in her own bed, in her own house, where she likes to relax by curling up on the couch in her sweatpants and reading more recipes. But by that night, social media had pounced on her brief moment of spontaneity, making fun of her sequined jacket, her amazing technicolor coat, harping on how stupid and frivolous it is for a woman to be trying on clothes on the presidential campaign trail.

It’s not easy out there. You can’t expect much forgiveness on Lady Street. Yet Harris, as ever, is playing the long game. She often repeats her most succinct one-line pitch to prospective voters: “We’re going to need somebody who knows how to prosecute the case against this president.”

She packed a bag for New Hampshire: all dark suits.

This article appears in the May 2019 print edition with the headline “Kamala Harris Takes Her Shot.”

Comments

Comments are disabled for this post.